Pellatt Road

2020-11-22

In East Dulwich there is a Pellatt Road. I still don’t know how to pronounce it; a simple “pellet” seems most statesmanly. I’ve wondered where that name came from. It struck me as a person’s name, probably.

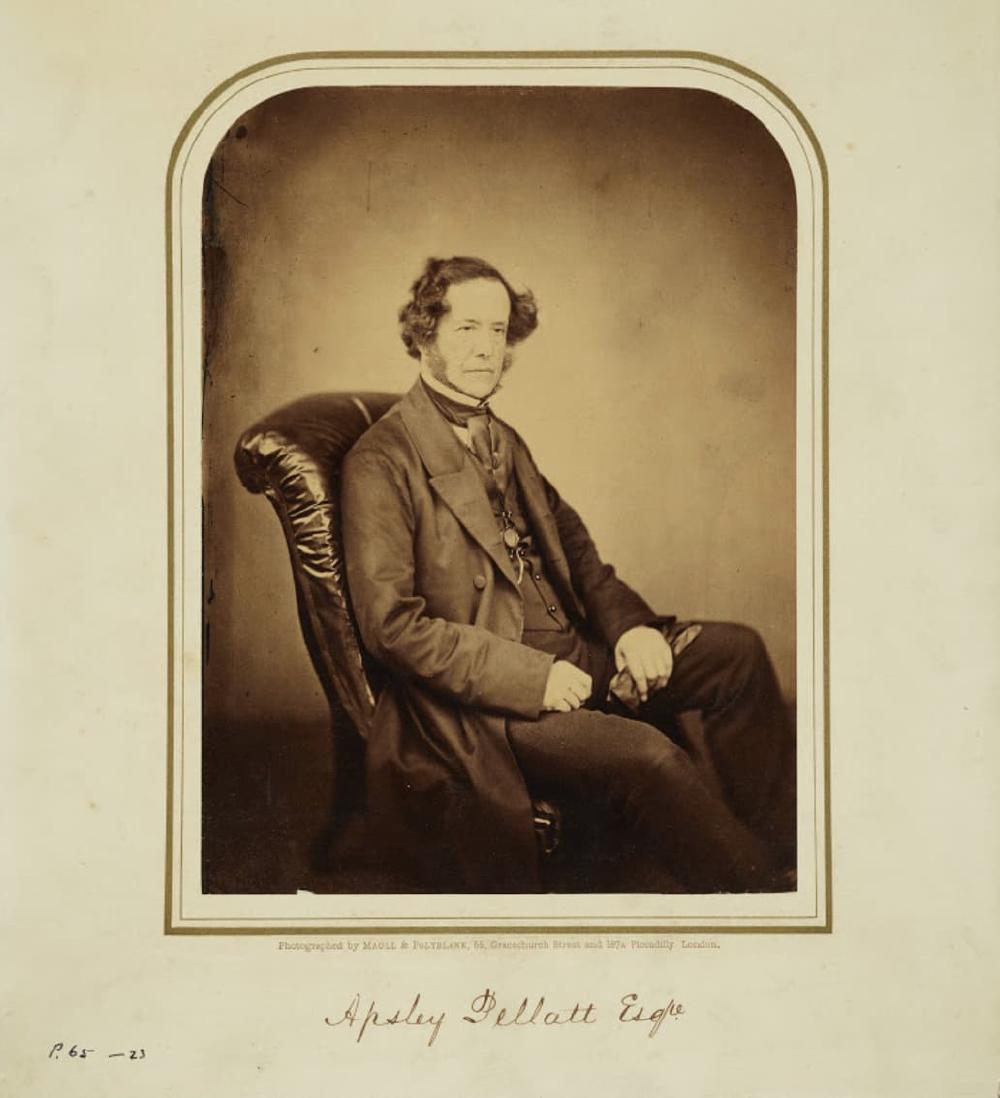

I started looking, and found an MP for Southwark who died a little before a plot called Friern Farm near the village of Dulwich in Surrey was bought up and replaced with a tidy horseshoe of early Victorian streets, one of which was named Pellatt Road. Taking that as good enough, I sank into a rabbit hole finding out about what life he led to get a street here named after him.

Apsley Pellatt Snr was born in 1763 to a man of the same name. His father (Apsley, obviously) was from Lewes, his mother Sarah was from Bermondsey. When he was twenty-five he married Mary Maberly. Her family were wealthy curriers (leather finishers; I had to look it up). Her brother John would eventually break out from the family business to form his own business, buying a mill in Aberdeen and supplying leather and linen good to the army who were busy fighting Napoleon in Europe. Apsley and his wife settled in his home town of Lewes, but his business was at St. Paul’s Churchyard.

In 1790 Apsley had his first son, who would become Apsley Pellatt IV, the main but by no means the only Apsley Pellatt in our story. That same year Apsley Snr bought a glass house on Holland Street. The Falcon Glass House was about a twenty minute walk from his business in the churchyard of St. Paul’s Cathedral. He would step out of his shop in the shadow of the cathedral, walk down Lugdate Hill and turn left down Blackfriars Road, past the Blackfriars Pub (which I have personally tried and can attest is worth a stop), over the bridge and through the warren of workshops that would have butted up the water’s edge on the south bank of the Thames. Nowadays, the Millenium Bridge would have halved the trip between his shop floor and his factory if there wasn’t a big Tate Modern sitting where his glass works should be. Anyway, Pellatt’s acquisition had been making glass for almost a hundred years up to that point and Apsley got to work getting to grips with the craft.

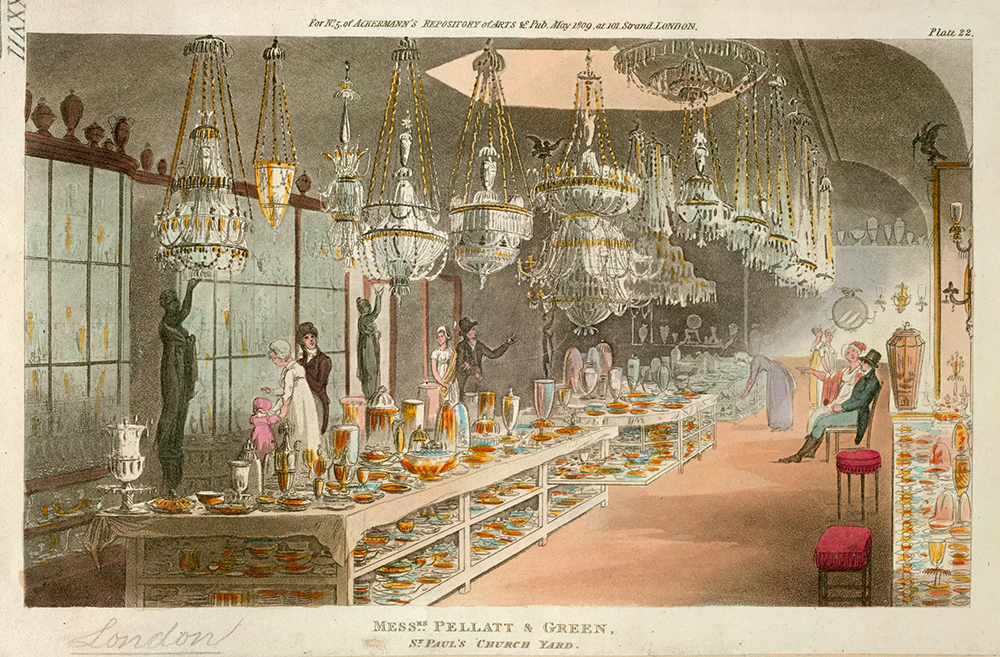

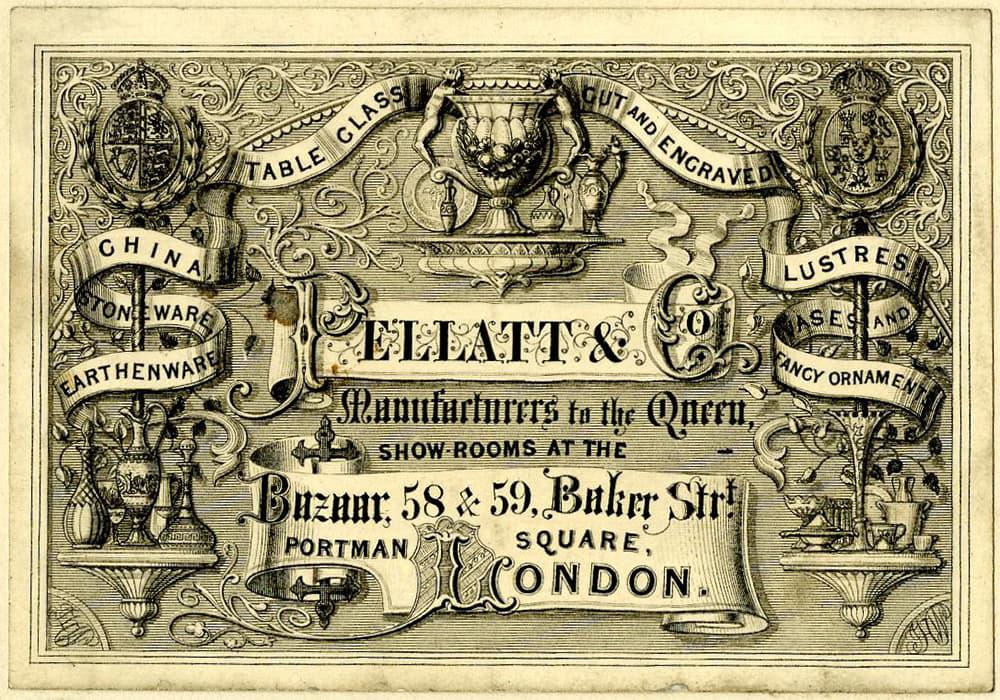

By the turn of the 19th century, Pellatt & Greens Co were a renowned glass manufacturer. They had their production on the south bank of the Thames and their showroom at No. 16 St. Paul’s Churchyard, with bazaars in two locations in Marylebone. Money from the slave economy powering the industrial revolution enabled grew the merchant middle class in the Georgian era, which in turn freed up money for ornaments and curios. It’s in that context you can imagine Pellatt & Greens show room servicing a rotating cast of upper middle class couples arguing about which luxury decanters and wine glasses would do. In a simple analogue to celebrities appearing with luxury products in advertisements today, Pellatt & Greens’s advertisements make it very clear they are “Glass Makers to the Queen”.

Britain had been fighting for supremacy on the seas for decades, be it mercantile or naval. Cargo ships and warships were a crucial backbone of the country. It seems Apsley Pellatt had one eye on his luxury goods business and another eye on dealing himself into the naval-industrial complex. In 1807, Apsley Pellatt took out a patent on the “illuminator”. This invention, basically a porthole, would be ideal for illuminating the dark and dingy lower decks of a ship. Its round, lensed glass would focus light into the interior as well as provide some more strength against getting smashed in by cargo jostling into it or rough seas pounding it.

This method consists in placing an illuminator in suitable apertures in the decks or sides of ships and vessels, and in buildings and other places, to answer as a window or skylight. This illuminator is a piece of solid glass of a circular or elliptical form at the base, but the circular form is the most productive of light, and the strongest against accident; it is convex on the side to be presented outwards to receive and condense the rays of light, and has a flat or plane surface on the inside of the room or apartment, which it is intended to light. It is or approaches to a segment of a sphere or spheroid; it is in fact a lens; both sides may in general be left polished, but where the illuminator is to be placed in a situation where any danger may be apprehended of it being acted upon as a burning glass, one side at least should be ground or roughed. Its size is various according to the purpose or situation for which it is designed, and its convexity is increased or diminished according to the side required. The ordinary dimensions are a base of about five inches diameter, to one inch and a half in height from the center of the base; the illuminator is fixed in a square or circular frame made of wood or of metal, with glazier’s putty or other cement.

For decks and other parts of ships, its construction is so managed by thickening the edges, as to render it capable or resisting any injury from the weight of goods of every description, and the beating of the waves of the sea in the ports and scuttles. It is let into the deck or other building with the convex part projecting above it, so as to receive the rays of light; it is fixed in the deck or other building either with or without a wooden or metal frame, according as the space wherein it is to be fixed will allow; a groove of only one quarter of an inch will be sufficient to keep it firm, and in a deck of three inches thick, one quarter of an inch is bearing enough; in decks of less substance, the bearing must be increased one-eighth of an inch. The under part of the deck or other building which forms the ceiling of the cabin or place must be sloped away all round, so as to form a small dome, that the rays of light may diverge in all directions; the like method is to be observed in the ports and scuttles of ships, or in what place soever the illuminator is fixed. By being fixed in a square or round frame, with or without hinges, it may be made to open and shut for the free admission of air in hot climates.

In dwelling houses, buildings, and all other places, it is far superior to the skylights now generally used, not being liable to accident or leakage, nor can water pass under what it is fitting into. For buildings it is necessary that one side should remain unpolished, as the rays of the sun produce the prismatic colours when shining on the illuminator; this precaution is unnecessary in ships’ decks, as the traffic on them in a short time grinds or roughs the upper surface, but in no degree to prevent the effect, but if any thing conveying a more pleasing light under ground, vaults, and cellars, wherever any communication may be made with the open air, may also be lighted with this Invention, excepting only where from its situation it may be liable to injury from the passing or repassing or horses, &c

The illuminator will also prove a very important substitute for the glass now used in lanthorns for lighting the powder magazines in ships of war, care being taken that the convex side be in the inside of the lanthorn where the light is placed.

Apsley Jnr joined the business in 1811, when he was 21. Presumably he’d been away getting an education, given his later authorship of scientific engineering works and political radicalism. It seems he spend his twenties taking over responsibility for his father’s business as the elder Pellatt gradually aged into retirement, and trying to start a family. In 1814 he married Sophronia, who died just a year later aged just 23 and making him a painfully young widower. Seemingly he was able to put himself back together, or he felt the pressure to find another wife to create an Apsley V with. He married Margaret Elizabeth Pellatt in 1816, and had a son named Apsley in 1819.

The Pellatt and Greens Company were a community fixture by then. They donated the considerable sum of twenty pounds a year to the Association for the Relief of the Manufacturing and Labouring Poor, a charitable record that later works to Apsley IV’s credit. The local papers record a couple of small misfortunes that befell the company. The theft of a large quantity of their glass is reported from a cart in the City of London one Thursday night in early February 1818. The next Tuesday, the unfortunate culprit, Joseph Napphali was found in the apparently notorious Weavers Arms in Finsbury after trying to hawk the stolen glass in Petticoat Lane. The Weavers Arms was demolished in 1986 and the site has been subsumed as part of the enormous UBS headquarters in the Liverpool Street/Broadgate Circus megacomplex, so arguably still a den of thieves. Anyway, he was brought before the magistrate in Worship Street and presumably went down.

In 1812, Mr. Fox, a clerk from the Pellatt and Greens manufactory was found dead on Blackfriars Road in the early evening. He had clocked off and was presumably on his way over the bridge to check in at the manufactory over the river and head home. The coroner, possibly eager to similarly clock off and head home, delivered the verdict: “Died by the visitation of God.”

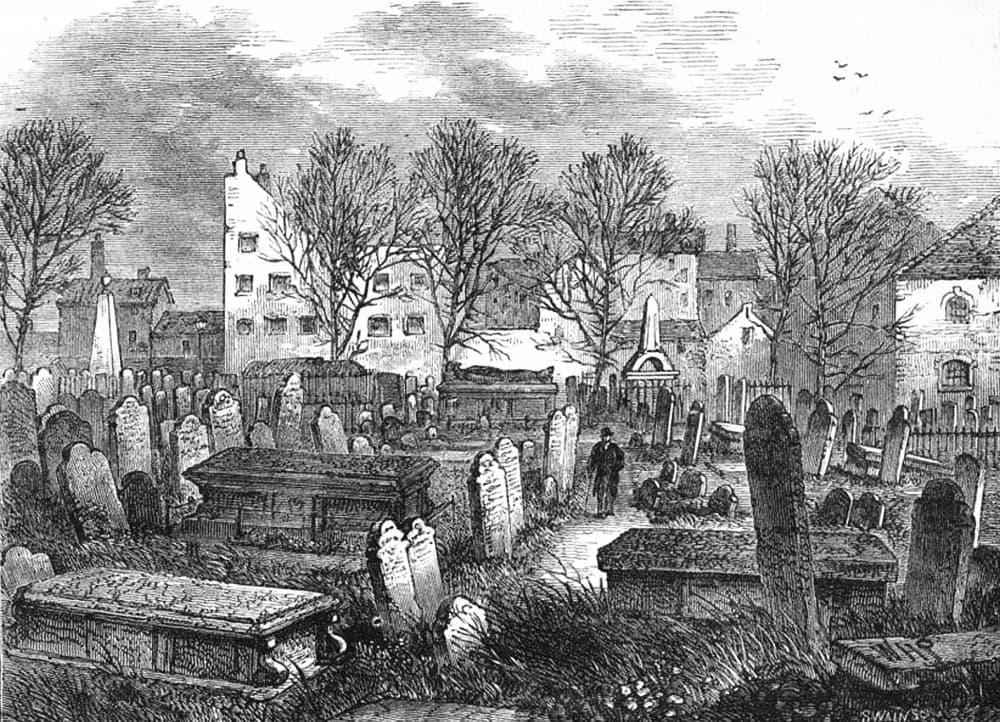

Apsley Pellatt IV’s mother, Mary Pellatt died in 1822 at the age of 54. Four years later her husband followed her. The senior Apsley Pellatt died in 1826 at the age of 63. He lived to see the entire reign of George III, the independence of the American colonies, the defeat of Napoleon at the battle of Waterloo, and the abolition of the slave trade, but missed the abolition of slavery itself by just a few years. He left fifteen children and a respected glass company. He was buried with Mary in Bunhill Fields in Shoreditch, which was dedicated as a public green space in 1853, and in which I used to go and sit and eat lunch when I was working for Depop in their Paul Street office. Somebody, perhaps the in-laws given how many Maberlys are buried in there, negotiated for them to be interred in the tomb of one Obadiah Boote along with a mix of well-heeled Georgians merchants. The side of the vault reads:

Apsley Pellatt Esq late of the St Pauls Church Yard & the Falcon Glass Works Dec 21 Jan. 1826 In the 63 Year of his age.

Elizabeth Pellatt Daughter of Apsley & Elizabeth Pellatt & grand-daughter of the above. Born Nov. 2. 1817. Died May 16 1834

Mrs Mary Pellatt. Wife of Mr Apsley Pellatt died Dec 14. 1822 Aged 54 Years

…A whole host of Maberlys omitted

Apsley Pellatt. Grandson of the above. Born Dec. 2 1819. Died May 29th 1839.

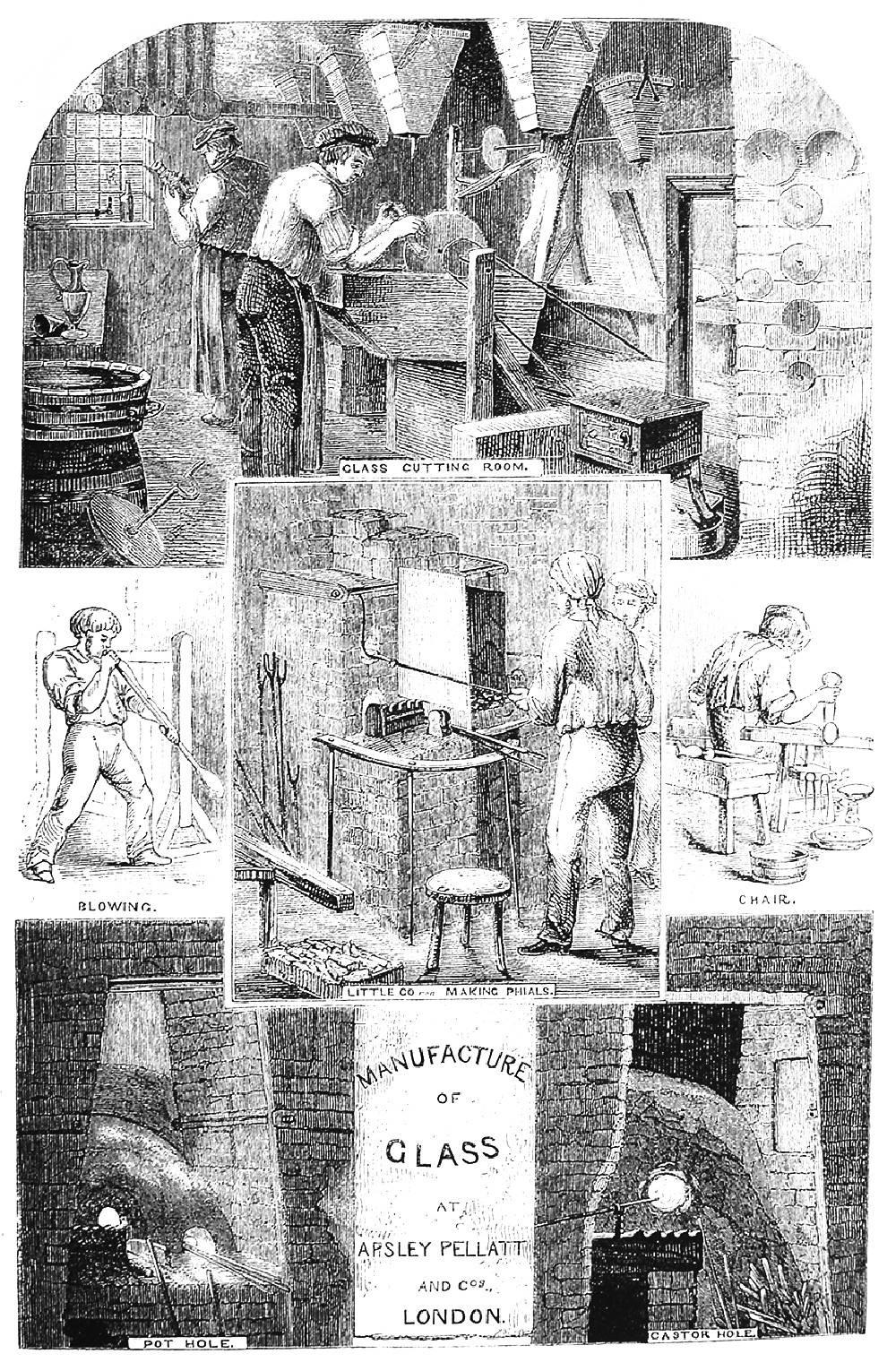

Apsley Pellatt IV took control of the company on his father’s death and renamed it Apsley Pellatt & Co. The younger Apsley took a keen interest in the scientific side of glass-working. Michael Faraday’s notebooks remark that a sort of laboratory for optics had been built on the Falcon Glass House premises in the 1820s.

Around this time, a (clearly very excited) journalist from a trade magazine came to visit the glassworks of Apsley Pellatt & Co.

The factory is situated in Holland Street … It is not the cleanest neighbourhood in the world, but we must not mind that: it is the glass-house we want, not the street: and if we wish for information, we must not travel in shiny boots and white kid gloves. The glass factory, then, of Messrs. Pellatt comprises several buildings necessary to the art, and occupies about three-quarters of an acre.

It is almost impossible to describe one’s sensations on entering this buildings for the first time. In the ordinary way, the visitor is generally shown the glass-house first. He is lost in wonder. He gazes around him upon the dingy walls, in the centre of which is the melting furnace, the chimney of which rises through the iron roof. He cannot reconcile the dimness of the place with the bright glow from the pot-arches or the dull radiance proceeding from the anncaling arch. He feels some little alarm as he sees dusky figures close behind him swinging about great masses of what appears to be red-hot iron.

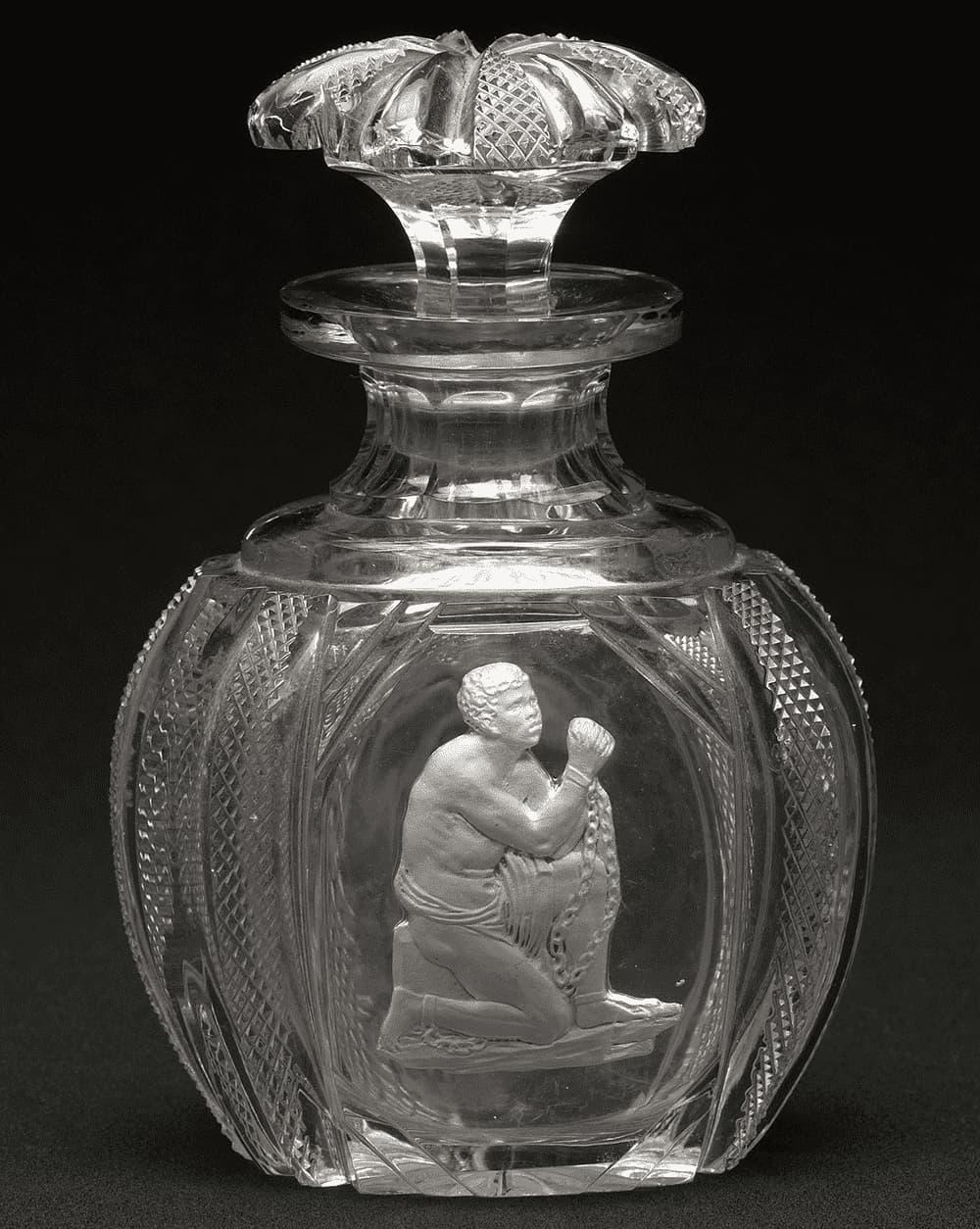

Apsley IV’s interest in the science of glass-working quickly yielded results. In 1819, he took out a patent for a process for encases medallions in glass. Not much later the Falcon Glass Works began producing sulphides. Sulphides (also known as incrustations) are glass wares that contain three-dimensional images, often busts of heroes or beloved relatives in military dress, known as cameos. Georgian London went through a fad for these cut glass memorabilia items and Apsley Pellatt Co profited from it by being early with the technology and producing a range of products: decanters, paperweights, bottles, jugs, mugs.

It seems Pellatt spent the earlier part of the 19th century refining his glass techniques for cameos and writing up his findings. In 1821 he published his Memoir on the Origin, Progress and Improvement of Glass Manufacture including Glass Incrustations.

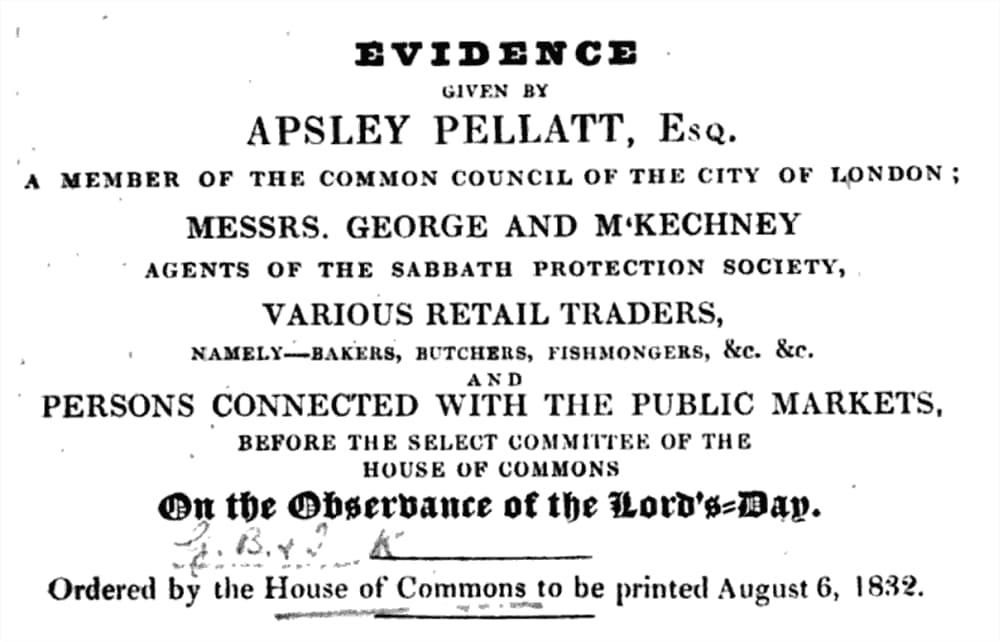

Pellatt was a political liberal. His father had donated serious sums of money to associations for the poor, and the younger Apsley did the same. His views on universal religious equality were relatively extreme for the time, and he wasn’t quiet about them. He joined the Common Council of the City of London, which makes sense given his position as a prominent merchant local business figure. He was also a member of a couple of couple of counter-cultural political organisations with the aim of securing religious freedom for all, and in particular for Jews. The Philo-Judaean Society aimed to remove some of the discriminatory actions against Jews in the markets in the City: laws limited the number of Jewish brokers in the Exchange, Christian Sabbath laws prevented Jews from opening their businesses in Farrington market on Sundays. Pellatt petitioned the City to give Jews freedom of the city in 1829. He proposed to increase the number of licensed Jewish brokers in 1830, and he made the case for the Jewish market sellers in 1832.

Sometime in the 1840s, Pellatt settled his family in Staines. That put his manufactory in Southwark, his showrooms in the City and Marylebone, and his home in Surrey. For reasons I can’t really fathom, Apsley Pellatt first ran as an MP in Bristol, in 1847. Perhaps he didn’t want to put his neck out in the City and threaten his business. His opponent in Bristol, a Mr. Berkeley, won handily. The City of Bristol was not ready to support a candidate who was for universal suffrage and religious freedom. In 1852 he tried again much closer to home. A piece in The Economist called The Coming Elections: Southwark and Finsbury gives us this:

Though the time for dissolving Parliament is not yet fixed, the din of the coming elections is heard in almost every part of the country. In many places we regret to announce there are divisions amongst the Liberals, who, having obtained a triumph, now seem, like other victorious parties, to be inclined to quarrel about trifles amongst themselves. In Southwark, for example, Sir William Molesworth is assailed, and Mr Apsley Pellatt, a very worthy man, an excellent reformer, a promoter of peace and good-will, offer himself to contest the borough in the interest of one section of Liberals against another.

So Pellatt has decided to try and outflank the already Liberal constituency of Southwark. He was running as a Dissenter (a Protestant to Protestantism) in a borough with a good number of them, a Liberal in a safe Liberal seat, and as Aspley Pellatt the renowned glass merchant and employer in the area. His professional organisation, the Institution of Civil Engineers, are happy to report:

His influential position in the Borough of Southwark, where he so long resided, brought him into prominence as a politician.

…

At the general election in 1852, Mr. Pellatt was himself returned to that constituency, and he remained a useful member of the legislature for five years, interesting himself in various commercial questions, and voting in favour of all measures of reform.

They’re clearly proud of their own boy. Unfortunately for them, with his entry in the political life came his retirement from Apsley Pellatt Co, which passed to his brother Frederic and became Pellatt & Co. The trend for cut glass memorabilia faded away with the ascension of Queen Victoria. You could blame that for the gentle decline of the Pellatt & Co enterprise; a lot of the records seems to rather cruelly imply Fred was to blame.

Apsley lost his seat in the 1857 election, and he lost again in 1859. I saw somewhere that he was a political victim of a banking corruption scandal (as opposed to an actual victim) in that 1857 election and presumably never managed to shake that. By the time he lost the 1859 election he was 68 years of age. His father had died at 63. Apsley Pellatt IV made it to 72. He fell ill around the 10th April 1863 and it looks like he headed for treatment in Balham. He died “of paralysis” there on 17th April. His wife Margaret Elizabeth Pellatt followed him eleven years later and they were buried together in Staines.

For hundreds of years, East Dulwich was divided from Dulwich proper along the historical boundary of the Friern Manor and Dulwich Manor, the latter transforming into a College town from the gifts of Edward Alleyn in the 17th century. Lordship Lane roughly traces that boundary, and put East Dulwich just over the border in the borough of Southwark. While the esteemed Southwark businessman, scientist, reformer, and politician Apsley Pellatt was being interred in Staines, builders were bidding for the contract to transform Dulwich from a village in the Surrey countryside into a London suburb.

In just a few years, train lines spread down into the area and housing enclosed the old hamlet. It seems the building of Pellatt Road’s surrounding streets was at least nearly completed by 1882, when the Heber Road School was dedicated. In those years then, some builder or councilman was looking at the new plan of roads on the old Friern estate and cast an eye at the electoral history or perhaps was a Radical type, or maybe just knew somebody who had worked at the Falcon Glass House on Holland Street, and threw Apsley Pellatt’s name into the mix.

Links

- Apsley Pellatt at The British Museum

- Apsley Pellatt III’s patent for the illuminator window

- Apsley Pellatt’s election in the London Gazette and the Annual Register

- Lesley-Anne McLeod’s blog on Pellatt and Greens

- Apsley Pellatt in the Glass Encyclopedia

- The Pellatt Pedigree

- Pellatt’s failed election in Bristol

- The Economist’s Report of the 1852 Southwark Election

- Civil Engineers Report on the 1852 Southwark Election

- Pellatt and the Jewish community in London

- Apsley’s evidence to the Select Committee

- The emancipation cameo